Book Club Reviews on “Burning Bright” de Ana María Sánchez Mosquera

8 Dec 2024

1 Dec 2024

The Sieve and the Sand in "Fahrenheit 451" by Ray Bradbury

No Fireplace in the Empty Hearth but Caustic Fire

The section opens up with a saddened cadence of Montag’s reading to his wife from one of the books he has salvaged from the caustic fire. The setting is an empty house with barren walls that mirrors the emptiness of their lives. “The family” as Mildred calls her TV shows has been shut down.” The incendiary pace of the first section has suffused after the dramatic self- immolation of an elderly lady who would rather perish than forsake her literary treasures. No hearth is found here: the words Montag reads bounce off in the void of Millie’s soul.

Clarisse, the perceptive young woman, seemed to mirror a younger, more introspective version of Montag in the earlier section. In this one, Faber—the guardian of books—represents a potential vision of an older, wiser Montag. Driven by a frantic search for meaning, Montag embarks on a maddening journey of self-discovery as he strives to save the written word from oblivion.

“Memory like a Sieve”

Montag understands that by memorizing the books he can be the bearer of a holy grail and thus, contribute to save them. Indeed, before handing Beatty his treasured possession of “Ecclesiastes,” he tries to memorize it, but the words slide through his mind, distracted by the clatter of the tube and the disquieting jingles of a toothpaste commercial. Metallic, numbed, nulled … his mind is arrested by the devouring expediency of modern life:

“Guy's modern world counts on this inability to concentrate. This world he lives in without books has encouraged people to live for the immediate moment; it's a world of sound bites and expediency. By filling every place with mindless sound such as the advertisement jingle, people can't concentrate and do any serious thinking. If people can't think, they are much more easily controlled. This is just where society, and the government in the book, want people. By banning books, people's minds have been turned into sieves unable to hold thought.” Source; here

Logos: the first Word

"In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God." (John 1:1). “Word” translated from the Greek “Logos”

Logos / word embodies an unfleshed god that later turned into a human. Following the thread of this metaphor, it is noticeable that the book Montag is trying to memorize is the Bible, the word “par excellence.” Religious metaphors sprinkle “Fahrenheit 451.” Marcial brought to our attention the equation between Montag and St Paul, or the river that will later appear in section three, “Burning Bright,” with the river Jordan. Equally, the Harvard inmates he finds in the river jokingly acknowledge themselves as the Apostles (comments indebted to Marcial).

Montag’s recitation of Matthew Arnold’s Dover Beach to Mildred’s friends juxtaposes the dark, oppressive world surrounding him—marked by the relentless burning of books and the authoritarian surveillance of citizens—with a world of profound emotion, one that stirs and wrenches the hearts of those who struggle to bear the weight of genuine feeling.

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

Beatty, the fire brigade captain, humiliates Montag in a verbal duel laden with literary references, leaving Montag unable to respond. Reduced to silence, he succumbs to Beatty's rhetorical dominance, embodying the numbness that defines him throughout the first and second sections of the novel. It is only in the third section, during his journey down the river, that this numbness begins to dissolve in a symbolic act of rebirth (drawing on Marcial’s imagery of the river as a metaphor for renewal). Beatty’s pointed remark:“Who are a little wise, the best fools be” can be traced back to John Donne’s poem The Triple Fool (click on the title to read the full poem):

For loving, and for saying so

In whining poetry;

But where's that wiseman, that would not be I,

If she would not deny?

Then as th' earth's inward narrow crooked lanes

Do purge sea water's fretful salt away,

I thought, if I could draw my pains

Through rhyme's vexation, I should them allay.

Grief brought to numbers cannot be so fierce,

It is specially interesting to notice the two last lines where the power of the written word seems to be highlighted, for Donne, the poem will be a memento of his pain because it will be “fettered” in words but it will also be be liberating because as he puts his thoughts in words he will be released of their pain. Montag will be the wise fool because he did what he had to do by acknowledging that the books are more than stitched pieces of paper, they bear the immanence of the thoughts and knowledge of the writers that wrote them.

24 Nov 2024

16 Nov 2024

"Fahrenheit 451" by Ray Bradbury

How to live forever: Brushstrokes on the author

The author of “How to live forever” in Dandelion Wine, is now approached in what he deems his only sci-fi novel: "Fahrenheit 451. Check this interview here where most of the thoughts below mentioned have been extracted from:

Cándido proposed the reading of Fahrenheit 451 to the Reading Club and truly, triggered by his profound admiring of Bradbury which I / we absolutely back, we incorporated the novel into our program. A book on books being burned, censored, and banned is absolutely a must for book lovers, as Cándido stated. There is a long history of orchestrated book burning:

The Roman Empire burned up countless books over the course of its long reign. The first emperor, Augustus — objecting to books of “prophesies and destinies” — ordered more than 2,000 books to be reduced to smoke and ashes, according to “Book Burning” by Haig A. Bosmajian. One of the greatest losses of literature was at the Library of Alexandria, established under Alexander the Great in northern Egypt around 331 BC. The library was burned down at least three times over hundreds of years and is now permanently erased. At one point, the Library of Alexandria held over half a million documents from multiple nations, including present-day Syria, Greece, Persia, Egypt and India....Nazi Germany’s incineration of 25,000 “un-German” works on May 10, 1933, is perhaps the most infamous book burning event because photos and videos of the event can still be seen today. Source here

“Fahrenheit 451” unspins the dystopia of the world without books, where books are forbidden, burned, and may compromise the stakeholders.

Bradbury mentions in this interview how passion-oriented he is and how committed he had been to writing as a naturally driven force inside him: “I never worked a day in my life,” he adds that he followed a passion rather than a job. Aside from any intellectualization that might have broken the pace of his throbbing heart on a throbbing machine, Bradbury confesses himself as a self-taught man who has lived in libraries all his life. Libraries and books being burnt as well as his fantasies and admiration for the fire department where his uncle worked might have been the seeding bed for building a story arch. “Fahrenheit 451” started in the cellar of UCLA where typewriting machines could be rented for a few cents an hour. With a recently born baby and a small house, Ray Bradbury took a bag of dimes and embarked on the writing of an earlier version of “Fahrenheit,” which was completed in 9 days in 25, 000 words. “The Pedestrian” had him started in the writing among many other tales, or stories from his other books. In "The Pedestrian," he recounts an unfortunate encounter with a policeman who reprimanded him and his friend by mere walking and talking on the streets. This might lead to establishing connections with Montag's unexpected encounter with Clarisse at night time.

The title was brewed through inquiring research about the temperature at which paper burns. He contacted the Chemistry department to know but no certainty was given until he realized he could phone the fire department, it was then when the title was rendered: Paper burns at 451 Fahrenheit, and he repeated Fahrenheit 451.

10 Nov 2024

1 Nov 2024

"HE" by Katherine Anne Porter

ATONEMENT IN KATHERINE ANNE PORTER’S “HE”

Source for photograph:here

"He" is a short story by Katherine Anne Porter, originally published in New Masses in 1927 and then reprinted in Porter’s collection Flowering Judas and Other Stories in 1930. The story is about a poor American family. The mother, Mrs. Whipple, loves her second son best of all: a boy who is identified only as ‘He’.” (Source: Dr Oliver Tearle, Loughborough University)

Guilt, redemption, and the “search for meaning” as well as individuality in an intensely materialistic world, as Dr Tearle puts it, constitute the axis around which the narrative revolves. Similarly to all Porter’s stories, the selection of names is paramount: "Whipple" is an intestine disease caused by a bacteria (a very interesting connection brought forward by Begoña Rodríguez) all the more meaningful in the context of the story as the Whipples are blighted, not only due to their hypocritical maneuvering but also to the “sins of the fathers.”

The Whipples find it hard to make ends meet and “feed all the hungry mouths,” yet, Mrs. Whipple is rather more intent on preserving the “veneer of appearances” in front of the community and showing that she cares for her “simple-minded” son. Despite her apparent love and tribulations for him, she occasionally subjects him to dangerous and uncomely trials. Thus, her attitude towards him as well as her description of the boy are not precisely celebratory: “Rolls of fat covered Him like an overcoat, and He could carry twice as much wood and water as Adna.”

She forces him to perform "cruel" and dangerous tasks: He takes the suckling pig from its mother so Mrs. Whipple can slit its throat. He is equally in charge of fetching the bull that may dangerously and unexpectedly attack him. Mrs Whipple does not hesitate to take a blanket off him as she considers he cannot feel cold as his other two sisters do. A lavish repast will be offered to honour her brother so the look of prosperity might be kept. Yet “He” will be hidden, he wouldn’t come into the dining room, timidity alleged. “He” isn’t to be slighted...

Mrs. Whipple’s contradictory behaviours show that she is perhaps at a paradoxical crux pinpointed by “you know yourself it’s more natural for a mother to be that way. People don’t expect so much of fathers, some way,” being the keyword “expect.” Mrs. Whipple feels guilty and obliged to be utterly devoted to her son and pine for him either by societal pressure or to find atonement for what is called the “sin of the fathers” who might refer to some family “inbreeding” (as accurately highlighted by Paula Diz and Belén Tizón): “Blood and bad doings somewhere”.

The story’s religious undertones are unmistakable and as Dr Tearle points: The capitalized “HE” is likely to put us in mind …“Jesus Christ, since God and Jesus are often referred to as He or Him. And Porter’s ‘He,’ like Jesus, is poorly understood by those around Him and doomed to a life of suffering (including, we surmise, an early death).“A pious attitude of devotion in the face of opposition and even ridicule from others (such as theirneighbours and even, to an extent, Mr. Whipple).” Contrariwise to this extolling:

“the fact that the boy is referred to by His mother simply as ‘He’ denies him an identity and an individuality. Or, to be more specific, it both strips Him of individuality and makes Him stand out (in the worst possible way) as an individual because He is being treated differently. If one of Porter’s great themes is the struggle for identity in the modern world, He has a tougher struggle than most.” (Dr Olive Tearle)

We are never granted access to the boy's emotions. Unlike in Faulkner’s “The Sound and the Fury” (enthralling comparison brought about by Mónica Rodriguez) where Faulkner gives us access to Benjamin’s convoluted thoughts through the narrative technique of stream of consciousness, in Porter’s story, we hardly have access to the boy’s thoughts and feelings.

Yet,towards the end of the story, tears roll down his cheeks when He is to be sent to the County House as a result of a fall and constant seizures: he is sneaked in a carryall so the neighbours will not tell. Mrs Whipple intones “You don’t feel so bad, do you?” at the same time that a sense of relief overpowers her thinking that she might now have time for the girls.

26 Oct 2024

Katherine Anne Porter's "Magic"

"Yes, and then?"

Scherezade in Porter's Magic

It never dawns in New Orleans

In medias res, and almost in an uninterrupted monologue technique, “Magic” opens up in the boudoir of Madame Blanchard with the the horror-account of Ninette’s story through the eyes of Madame Blanchard’s maid in a Scherezade-like nested story. The maid renders the narrative in a dissembling matter-of-fact way triggered by the hearsay of Madame Blanchard’s bewitched linens. The story arc of magic conjoins the frame narrative and the story told through a series of mirrored-reflective events that bring both the maid and Ninette together as well as Madame Blanchard and the Madam of the fancy house (brothel) against a backdrop or racism, abusive authority, exploitation and violence, with money at its core. Madame vs Madam (only an "-e" separates both names).

William L. Nance in “Katherine Porter and the Art of Rejection” quoted by Michael Hollister points that “Ninette is pathetically impotent to free herself. Since the reader knows her only as a victim, however, the emphasis of the story i n not only in sympathy but the horror of the situation. Source https://www.amerlit.com/sstory/SSTORY Porter, Katherine Anne Magic.pdf

Brushing and stroking Madame Blanchard’s hair, the maid recalls her times in the brothel where she encountered Ninette. Ninette will not easily yield to “Madam's” demands of handing back the money given by the clients. While “Madam” subtracts her brass cheques (“A brass check was the token purchased by a customer in a brothel and given to the woman of his choice”), she sneaks some money under her pillow. Violence ensues, and a terrible determinism frustrates her escape only to bring her back through magic spells.

Ninette rolls in blood to fall at the feet of our narrator and the two narratives collide in a room in a brothel in New Orleans:

“The madam began to shout, Where did you get all that, you …? and accused her robbing the men who came to visit her ...The girl, said, keep your hands off or I’ll brain you: and at that the madam took hold of her shoulders, and began to lift her knee and kick this girl most terribly in the stomack, and even in her most secret place ...and then she beat her in the face with a bottle, and the girl fell back again into her room where I was making clean” (page 40)

Madam's cook plays the cruel magic spell that brings Ninette back to an inescapable determinism: “For the cook in that place was a woman, colored like myself, like myself with much French blood just the same, like myself living always among people who worked spells” (41). The iterative use of "myself" in a threefold litany draws Madame Blanchard's maid and Ninette's story together: magic rituals, abuse, violence and exploitation knit both. "When she comes back she will be dirt under your feet," the cook pinpoints. Madame Blanchard’s maid hears the click of her mistress’ perfume right after as well as a dull: “Yes, and then?" The tale is thus concluded: "and after that she lived there quietly."

Ninette and Madame Blanchard's servant both remain locked in their own worlds, a spiritual rather than physical entrapment as William L. Nance suggests:

“Ninette’s imprisonment is not mere matter of locked doors and barred windows, but an enslavement of the spirit. The spell has added symbolic resonance to the young’s prostitute degradation.”

No story will grant our Scherezade her freedom.

19 Oct 2024

"María Concepción" by Katherine Anne Porter

The Archeology of María Concepción

Source for photograph: here

María Concepción constitutes the first story that Katherine Anne Porter finished and published after 30 other stories she had previously discarded as mentioned in this interview: “Day at Night: Katherine Anne Porter, Novelist and Short Story Writer.” Katherine Anne Porter lived for a long time in Mexico, the setting to this short story.

“She walked with the free, natural, guarded ease of the primitive / woman carrying an unborn child. ….She was entirely contented. Her husband / was at work and she was on her way to market to sell her fowls” (María Concepción page 3)

María Concepción overlooks the spines and thorns that lie ahead in the dusty road in perfunctory daily work. There is no time to rest in the shade nor to practically “draw the spines from “ her feet. This sturdy ancestral woman advances forcefully, purposefully, regardless of the swollen limbs of dying fowls that sling back on her shoulder to be sold and gutted. There is no time for emotional haphazardness. Picture her, black eyes shaped like almonds and a clean bright blue rebozo, vanishing in an arid landscape brushed by the winds that shape the jacals ( a type of hut / shelter) which challenge the laws of gravity.

María Concepción resonates with a stream of religious metaphors. She proudly saved some silver coins to be "married in church" and have the bans for three days unlike the other villagers that must marry behind the church, she will kneel to the Virgin of Guadalupe and sneer at Lupe’s unorthodox healing ways that resemble those of a charmer. María Concepción bottles up anger and retaliation as she discovers Juan Villegas (her husband) and María Rosa’s dalliance and swears to kill them.

Givens (manager of the archeological dig) for whom Juan works wounds the earth in search for archeological remains with the precision of the scalpel. The locals wonder about this useless uprooting as it brings no monetary profit unlike their totemic souvenirs in the village. Earth and Maria Concepción are corroded, broken up, rampaged. She barrenly miscarriages, while María Rosa bears fruit. María Rosa and Juan return to the village after enlisting in the army, deserters, outcasts are forsaken by a community that retorts to them.

María Concepción mangles the body of María Rosa in an acrimonious devastation of a repeatedly thrusting knife. María Rosa, who had enough love and enough honey lies in a coffin, pitiless. A silent acquiescence on behalf of the community endorses María Concepción. This ancestral primitive woman forcefully steps forward and appropriates María Rosa’s baby, a changeling of the fairies or a miraculous conception to whom she believes has the right to.

13 Oct 2024

Agon

“Life is too short to read a bad book”

We kick off this reading season by posing some questions that seem to be easy to answer at first sight but that often leave us brooding in a speechless limbo.

How can we tell if a book is good literature? How do we apply James Joyce’s paraphrased quote, “Life is too short to read a bad book,” and, therefore, commit ourselves only to the good ones?

An idea lingers and is branded in my mind: a book has to be at least twenty years old to be read, and a book must survive the passage of time. I tried to trace this statement back, bearing in mind that it could be attributed to a German philosopher, a rephrase of Kierkegaard, perhaps, but, faded memories turn to be cloaked landscapes of veracity. The wonders of the internet, I came across Clifton Fadiman.

Fadiman was an American intellectual, editor, and literary critic. He seems to have made this statement in his anthology The Lifetime Reading Plan, where he recommended classic books for readers who wanted to enrich their knowledge of literature. The idea behind the statement is that a book's enduring value is demonstrated if it continues to resonate with readers for at least twenty years after its publication.

Apart from the test of time, what makes a book good? Compelling characters? A good opening? A unique style? A remembrance? Visceral emotions? We have puzzled out what we consider gripping books, books we detested, and revisited.

In “The Sound Inside,” a play by Adam Rapp, Bella Baird, one of her main characters, a fictional professor of Creative Writing at Yale University, points out that good writers leave it to the reader to develop characters with very few traits explained in their imagination. Salinger did not expand much on Caufield, and just by referring to his patch of gray hair and height, the reader has “thoroughly formed him in our minds.”

We try to traverse the bridges of reality to fiction and participate in Bella Baird’s creative writing workshop by picturing ourselves as third person characters in books perhaps written by Margaret Atwood, Mark Twain, Shakespeare, Jane Austen, Margaret Lawrence, Manel Loureiro, Ian Fleming. Only a trait is allowed for the sake of imagining the innards.

Our characters have mouths like floodgates, a passion for rough and grey Galician seas, fond of spy games, eager walkers; our characters will light rooms with bright and cheery dispositions, will be endowed with deceptive smiling eyes, daring dreamers with darker sides, creative selves that keep themselves to themselves in reserved ways; characters that blush at dawn with the ease of a rose kissed by the sun in Shakespearean fashion and cling onto to the nostalgia of bygone times.

(Thanks to Rosa, Salomé, Cheli, Sonia, Antonio, Servando, Mónica, Belén, Paula, Cristina, Marcial…)

This way we kick off, thinking about what makes a good book, some visceral feeling, a unique style, compelling agonistic (from the Greek “agon”: competing) characters, the language, surviving the passage of time, the clawing of it onto the skin, the talking about it, the resonance of it in our selves, the power of language ..

Sources consulted:

https://www.masterclass.com/articles/the-elements-of-a-good-book

How to know if a book is great: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5i52Aqso9Tk

18 May 2024

7 May 2024

28 Apr 2024

21 Apr 2024

All the World's a Stage

Duplicitous Nature

in Shakespeare’s “The Merchant of Venice”

I hold the world but as the world, Gratiano,

A stage where every man must play a part,

And mine a sad one.

(Antonio, Act 1 Scene 1)

Source for photo: Here

Source for photo: HereShylock, a victim or a villain? Women, empowered or suffused? Is the bond of friendship more powerful than love? Hazard or destiny? Human law or divine justice? Money or Love? Venice and Belmont.

Two Settings

“Venice: the thriving hub of international trade, inhabited by those involved in the cut and thrust of business and commerce. // Belmont: an imaginary setting, a civilised and romantic place, home to the gracious Portia” (Source: Oxford School Shakespeare, “The Merchant of Venice,” 2006)

Money?

In Act I of Shakespeare’s “The Merchant of Venice, “ fortune, which in Shakespeare may mean “luck” as well as “wealth,”grants Antonio a victory by rendering him “Vailing (mast-lowering) Andrew” (Spanish galleon from Cádiz captured by the British). Antonio introduces a debate at stake between material wealth and “ventures not only in one bottom “trusted.”

Fortune / Free Will / Fate / Hazard

Solanio sways from the material to the more elated explanation of presupposing love as the cause of Antonio’s “sadness” or “haziness.” Antonio's continued denial unravels deeper, while Solanio contemplates the immutable truth that our essence is shaped by the cards of fate dealt by nature." ”Nature had fram’d strange fellows in her time; “ Hazard (used in its etymological sense as "randomness") and fate contest to pull characters in divergent paths of understanding.

The choice of caskets is another good example of how hazard, destiny and free will mesh with each other. Portia cannot choose whom to marry, it is only one of the gold, silver, and lead caskets chosen by one of her suitors that will decide her destiny as commanded by her father. Yet, this choice has been contrived by him.

Friendship or Love?

As the play unfolds, Antonio places high stakes on his friendship with Bassanio by offering to accept a contract with Shylock bidding his own life as commodity, a pound of flesh will be cut if he fails to “forteit the bond.”

Equally, friendship surpasses love when Bassanio is ready to dispose of the betrohal ring that Portia offers him as token of their love in exchange for Portia’s services, disguised as a lawyer, in defense of his friend, Antonio. In the amorous subplots, bonds and betrayals ensue. Jessica will be ready to reject his father, and his religion for the love of Lorenzo.

Villain?

In spite of his merciless cruelty upon Antonio, Shylock is also presented as a tragic figure: he is dispossessed of dignity, mocked at, and derided. His claiming for mercy speech turns the balance between villain or victim:

I am a Jew. Hath

not a Jew eyes? hath not a Jew hands, organs,

dimensions, senses, affections, passions? fed with

the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject

to the same diseases, healed by the same means,

warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer, as

a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed?

if you tickle us, do we not laugh? if you poison

us, do we not die? and if you wrong us, shall we not

revenge? (Act 3, scene 1, lines 53 and following)

Women empowered or suffused?

Portia crowns Bassanio lord of her house and heart when radonmness has led him to choose the lead casket, the one that contains the portrait of Portia and the one that will grant him her hand.

Myself and what is mine to you and yours

Is now converted: but now I was the lord

Of this fair mansion, master of my servants,

Queen o’er myself: and even now, but now,

This house, these servants and this same myself

Are yours, my lord. (Act 3, scene 2, lines 165 and following)

Yet, Portia will not relinquish her position of power, “lord of her house,” and disguised as a “lawyer,” she will administer justice to settle the case between Antonio and Shylock. Possible inferences about Elizabeth the Queen might actually be embodied in the character of Portia.

Women trespass the boundaries allotted to them as daughters (Jessica), home-ridden partners as well as the natural barrier between daylight and night time when they rove streets. Women in Shakespeare’s time were played by boys: this double transvestism, boys dressed as women, who dressed as boys remains puzzling as to the role women played in Shakespeare’s works.

15 Apr 2024

"The Merchant of Venice" by William Shakespeare

INITIAL THOUGHTS

26 Mar 2024

17 Mar 2024

"The Piano Player" and "A Little Burst"

"THE PIANO PLAYER " AND "A LITTLE BURST" de Ana María Sánchez Mosquera

10 Mar 2024

"Throwing Ordinary life off Kilter"

Elizabeth Strout’s “Olive Kitteridge”

Source for title phrase here

Source for image: here

“Elizabeth Strout’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book in 2009 “Olive Kitteridge” is not strictly a short story collection, but rather a novel with carefully drawn vignettes of different lives lived in a small fictional community in Crosby on the coast of Maine, a quintessentially New England town. Uniting them all is the formidable figure of Olive Kitteridge, a school math teacher and the wife of a pharmacist. A larger-than-life character, she is at the centre of several stories and peripheral in others” Source: here

Alice Munro described Elizabeth Strout’s novel as “shining integrity and humor, about the bravery and hard choices of what is called ordinary life.” As Reshma Ruia states, “these are the quiet dramas that can throw an “ordinary” life off kilter, one wrong decision or choice that can alter the entire landscape of a life.” Strout reveals loneliness, broken hearts, suicidal drives, ageing, disappointment, the hunger for love and the fact that no one knows everything (“A Little Burst”). In “Starving,” she voices a centripetal axis that may pull these lives ashore, in the words of Winston Churchill: never, never, never, never give up.

The towering, ominous, bulky, and almost statuesque Olive Kitteridge, “ never in anyone’s memory inclined to be affable, or even polite ...”("A Different Road “128) that reveals herself through the story arc hardly appears in the opening story “The Pharmacy.” It is the eyes of Henry that usher us into the novel and through Henry we hear and see Olive. It is in this silence, observed from outside, and from the naïve insecure orderly world of Henry that her character starts to emerge as a powerful binding force of this coastal community. It is in Henry’s fears, pettiness and insecurities that we learn of Olive’s strength, independence and sturdiness.

“For many years Henry Kitteridge was a pharmacist” opens the chapter “The Pharmacy.”The reference to the span of time underpins the paralysis that some of the inhabitants of Crosby resonate with. Seasonal changes occur: colour fading and blooming. Coming and goings of the inhabitants of Crosby run apace with the passage of time. Some elope, some stay stagnant and engulfed by their little and big bursts (nod the chapter that bears the title "A Little Burst"): “You get used to things without getting used to things.” The elopers are missed and the ones that remain gaze empty-eyed through windows of cars, houses, and local stores. Henry’ s sense of self-complacency in his small pharmacy world contrasts with the shady description he makes of his wife:

“Retired now…. He remembers how mornings used to be his favourite, as though the world were his secret, tires rumbling softly beneath him…. The ritual was pleasing, as though the hold store...was a person altogether steady and steadfast.”

Objects, places seem to vividly shape the souls of the community. The piano in “The Piano Player” is not just an instrument, it is a character in the room. Whereas Henry shines in his small orderly world of vials caressed by a dappled sun, Olive first appears as “And any unpleasantness that may have occurred back in his home, any uneasiness at the way his wife often left their bed to wander through their home in the night’s dark hour...” (2). He watches that she does “not bear down too hard on Christoper.”

Henry’s infatuation with his pharmacy assistant, Denise, is peremptorily accepted by Olive. She shifts from derision”Handwriting is as cautious as she is ...she is the plainest child I have ever seen. With her pale coloring, …”(13) to indifference. Yet Henry acknowledges this powerful binding to Olive as a bastion of his life “...women are far braver than men. The possibility of Olive’s dying and leaving him along gives him glimpses of the horror he can’t abide” (18). As the possibilities of a liaison with Denise fleet before his eyes, he desires Olive “with a new wave of power. Olive’s sharp opinions, her full breasts, her stormy moods and sudden, deep laughter unfolded within him a new level of aching eroticism” (11). It is Henry’s tantalizing affair that reveals Henry’s own fears of solitude: “You’re not going to leave me, are you?” (he asks Olive).

25 Feb 2024

14 Feb 2024

"A poet in Mars: The Martian Chronicles by Ray Bradbury"

A book Review by Cándido Pintos Andrés

"A poet in Mars: The Martian Chronicles by Ray Bradbury"

Photo by Cándido Pintos

Rather than just an author of Science Fiction, Ray Bradbury is a writer in capital letters. In The Martian Chronicles, Bradbury shows us a collection of short stories of deep reflections on humanity and society, with the disguise of the colonization of Mars, when he is really talking about destruction and decay. Along the book, and apparently through the different expeditions to Mars, the author addresses the problem of racism, religion, the expansion of capitalism, the machine-age utopia, the future of technology, loneliness and solitude. In fact Mars, as the multiple rockets of the story, is just a means and the book could be entitled The American Chronicles with just a few changes and new descriptions

But he is also a visionary, and his stories are a showcase for both future technology (“Mr K himself in his room, reading from a metal book with raised hieroglyphs over which he brushed his hand, as one might play a harp. And from the book, as his fingers stroked, a voice sang, a soft ancient voice, which told tales ..”) and the threats posed by this technology against its creators (“The house was an altar with ten thousand attendants, big, small, servicing, attending, in choirs. But the gods had gone away, and the ritual of the religion continued senselessly, uselessly”)

Ray Bradbury writes with evocative language and masters creating emotional atmospheres with a prose touched by poetry. If not among the best, one of the most influential writers of his generation, inside and even outside the literary world, despite the fact that “We earth men have a talent for ruining big, beautiful things.”

Cándido Pintos Andrés

9 Feb 2024

Of Mistresses, Coyness and Metaphysics

John Donne’s “To his Mistress Going To Bed” (1669)

and

Andrew Marvell’s “To his Coy Mistress” (1681)

This post will aim at providing a comparative insight into John Donne’s poem “To his Mistress Going to Bed” (1669) and Andrew Marvell’s “To his Coy Mistress” (1681), both considered Metaphysical poets. Both poems are addressed to “their mistresses” rather than their “ladies,” or “wives.” The word “mistress” had different connotations at the time:

‘Mistress’ in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries normally designated a woman of higher social standing without any marital connotation, whether married or unmarried. It could also be applied to women of dubious sexual reputation. (Paraphrased from: History Extra and Mistresses and marriage: or, a short history of the Mrs )

Both mistresses constitute the target of their lover’s amorous requests so they can win their favours regardless of whether married or not, whether they are of high-standing or dubious sexual reputation. They are both the objects, the commodities, the target of the poetic voice verbal pyrotechnic. In Donne’s, the poetic voice exhorts his mistress to go to bed with him, and in Marvell’s, the poetic voice beckons his mistress to seize the day and yield to his requests because they have not “the world nor the time.” Marvell’s poem elaborates on the trope of “memento mori,” the urgency to seize the moment, given the transience of human nature.

In Donne’s poem, the convincing arguments and elegiac tone ( wooing his mistress favours) lay grounds for his verbal witticisms. He juxtaposes warfare imagery (foe, labour, breastplate) with Petrarchan deconstructed idealization: “heaven’s zone glistering but a far fairer world encompassing,” “the happy busk” he envies and that reveals “such beauteous state.” The erotic blends with the religious, as seen in the "hallowed temple" or "Mahomet's paradise." His mistress is envisioned as a new found land, his America. The commodification is rounded as she becomes a territory to be explored, a land to be conquered. After making his case, and on apparently false pretense of equity, the poetic voice instances his mistress to: “show Thyself; cast all, yea, this white linen hence, Here is no penance, much less innocence” and “To teach thee, I am naked first.”

In Marvell’s poem, the word “coy” indicates that perhaps no strenuous convincing argumentation will be needed. “Coyness” makes allusion to false pretense of shyness. The poetic voice makes a case about time and the transience of life, “memento mori,” and therein, the need to make most of her youth, “thy skin like morning dew” and cast away her “long-preserved virginity.”

“Had we but the world and enough time ….But ,,,,” they don’t and “while the youthful hue //Sits on thy skin like morning dew” (while she is still young) “Let us roll all our strength and all / Our sweetness up into one ball..”

As in Donne’s poem, we can also find references to far away lands: the Indian Ganges, empires, gems, and precious stones, a nod to colonialism once more, a larger setting that taps into conquering and possessing. Religious imagery is present here as well as it can be seen in references to the flood, and the conversion of Jews. As a counterpart to these promises of love, there is in “To his Coy Mistress,” the urgency and the overshadowing presence of death as suggested in the “marble vault,” and the putrefaction of the “body”: “the worms shall try.” “They cannot make their sun / Stand still, yet we will make him run” ( a possible reference to “Phaeton and the Sun Chariot”, both an image of death and youth). Eros kai thanatos is a common literary motif: love and death go hand in hand.

Whether a more satiric approach in the case of Marvell’s “To his Coy Mistress,” or a more sillogystic analysis of emotions in Donne’s “To his Mistress Going to Bed,” both poems share the brazen irony, and the juxtaposition of impossible elements through metaphors and similes as well as the analytical approach of the spiritual or less tangible that define Metaphysical poetry.

4 Feb 2024

29 Jan 2024

27 Jan 2024

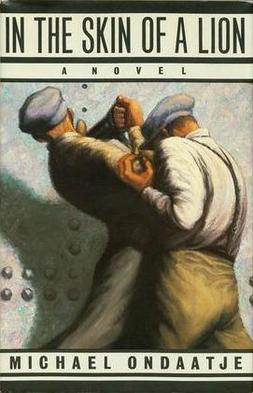

"In the Skin of a Lion" (Michael Ondaatje)

Caravaggio: more than a character in “In the Skin of a Lion" (1987)

by Michael Ondaatje

A Review by Begoña Rodríguez Varela

In Michael Ondaatje´s “ In the Skin of a Lion”, indeed, the independent likable character, painted in blue so he can camouflage in the dark and become a burglar, introduces himself as “ Caravaggio- the painter.”. The brilliant Baroque artist imbued his fabulous paintings with great theatrical drama and emotion thanks to his use of extreme contrast of darkness and light, his Chiaroscuro. However in this novel” the dark” reveals itself as a symbol of concealment, of secrecy, whereas the few sources of light, cattails, lanterns or candles, are symbols of life, of dynamism. Only at the end, the light floods in and everything comes alive.

Also, both authors, Caravaggio and Ondaatje share the idea that, to give a real picture of religious / historic events, those unhistorical forgotten people should undoubtedly be given their right place. All of them are also God´s people. Marginal and central figures together. Nice tableau.

Thereby the novel is made up of the intertwined, interconnected stories of a few of the members of those communities of migrants who participated in the construction of Canada: the waterworks, the tunnels , the bridge. It was the Commissioner Harris who had envisioned it. It was them who made his dream come true. No record was kept of those thousands who lost their lives then, though. Blankness.

Among those workers is Patrick Lewis, the protagonist, always in the shadows, alone, self-sufficient. He works as dynamiter of jam logs in the harsh countryside of Eastern Ontario and, then, as a searcher in Toronto, where he meets Caravaggio, the thief, for the first time. Afterwards, while in prison, Patrick would save his life. His first step towards authentic human connection. Friendship.

Later on, both solitaries, who fight against the privileged class violently, devise a plan together to blow up the waterworks. Now Caravaggio is the helping hand and Patrick, the one who swims in troubled waters.

However, after his encounter with Harris, the sunlight fully illuminates the scene. It is then that Patrick understands that no legitimate cause justifies violence, not even the death of just one human being, the Commissioner. Patrick finds his true identity ….at last.

Eventually , in broad light he starts a journey with Hanna, his late partner´s daughter to Marmora, where his first lover awaits him. But that will be the beginning of another story, different from Caravaggio´s, his friend, who disappeared in darkness.

By @caravaggio72

21 Jan 2024

"My Oedipus Complex" by Frank O’Connor (1963) and “Araby” by James Joyce (1914)

Fantasies at War

My Oedipus Complex by Frank O’Connor (1963) set in the close of World War I and Joyce’s Araby (Dubliners, 1914) set in Dublin in times of cultural and religious colonization of Ireland by Great Britain (Pedram Manieem, Shahriyar Mansouri) revolve around stories retrospectively rendered from the perspective of childhood. Lines can be drawn between both stories as to how the narrators´ perception of the world is presented with irony and an underlayer of political, social and economic circumstances.

Larry’s father comes and goes, unnoticed, like Santa Claus in his uniform, disguised in this fantasy, Larry copes with his father’s “mysterious entries and exists.” The war, “ he says, “is the most peaceful period of his life.” The absent father, noticeable for his “amiable inattention,” returns home in the aftermath of the war and ”usurps” his place in the fondness and attachment he feels towards his mother. He must keep quiet, not disturb his father. He is ostracized from the thalamus. It is the first time he hears those “ominous words,” “talking to Daddy.” God is to be blamed for listening to his prayers. Economic hardships wax the tension in the family: no more money at the post office and a bedridden unemployed dad that suffers from shell shock (post traumatic syndrome suffered by many soldiers affer the first war) coalesce to pinpoint the paralysis of the times. An epiphanic moment occurs when the new baby arrives and Larry and his father meet in their own displacement from the mother’s contesting attention.

In James Joyce’s Araby, the protagonist lives under the aegis of his uncle and aunt in an equally oppressive atmosphere as the opening of the short story illustrates, blindness and imprisonment being metaphors for it:

"North Richmond Street, being blind, was a quiet street except at the hour when the Christian Brothers' School set the boys free."

"On Saturday morning I reminded my uncle that I wished to go to the bazaar in the evening. He was fussing at the hallstand, looking for the hat-brush." (“Araby”)

See the political implications of this quote in this other passage from “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man” by James Joyce: Dante [his grandaunt] had two brushes in her press. The brush with the maroon velvet back was for Michael Davitt and the brush with the green velvet back was for Parnell." (A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man)

"I'm afraid you may put off your bazaar for this night of Our Lord."

The narrator’s fantasy of “Araby,” as an exotic escape from this darkness is already frustrated: politics, religion and oppressiveness will impede the fulfilment of his desires. He is doomed from start: his uncle is late for him to go to the bazaar, religion acts as a constraining force, and his pride will stop him from sparing his money out. The house where they live, he says, belongs to a priest. This priest refers to another short story “The Sisters” (Dubliners), connected with the sin of simony ( trafficking with religious objects).

The narrator’s first infatuation with Mangan’s sister will forcefully drive him to the bazaar, “Araby,” on an errand to buy her some token. Both Araby and his first love are wrapped in a foggy halo of fantasy:

I looked over at the dark house where she lived. I may have stood there for an hour, seeing nothing but the brown-clad figure cast by my imagination, touched discreetly by the lamplight at the curved neck, at the hand upon the railings and at the border below the dress.

When he arrives, the bazaar is closed. he listens to two men speaking in a foreign accent, “English,” and full of pride, he recoils from the prospect of buy anything.

I lingered before her stall, though I knew my stay was useless, to make my interest in her wares seem the more real. Then I turned away slowly and walked down the middle of the bazaar. I allowed the two pennies to fall against the sixpence in my pocket. I heard a voice call from one end of the gallery that the light was out. The upper part of the hall was now completely dark.Gazing up into the darkness I saw myself as a creature driven and derided by vanity; and my eyes burned with anguish and anger.

Irony, humour, innocence and growing pride understate and conversely highlight the frustrated fantasies that both narrators undergo in their harsh encounter with the social and political turmoil of the times.

Collaborative Work: An Angel at my Table by Janet Frame

Collaborative Work_ Reading Club_ Books Up! de Ana María Sánchez Mosquera

-

“Duplicity versus duality” in Margaret Atwood's Alias Grace by Begoña Rodríguez Susanna and the Elders by Artemisia Gentileschi “I felt...

-

“ The Bear,” a review by Begoña Rodríguez Varela “ Into the wind” By Marion Rose (Pic chosen by Begoña Rodríguez Varela) . Click here f...

-

“ HAMNET: Transfiguration of Life into Sublime Art” by Begoña Rodríguez Varela “ Hamlet and the spectre” By Eugène Delacroix : click ...