Sunday 28 April 2024

Sunday 21 April 2024

All the World's a Stage

Duplicitous Nature

in Shakespeare’s “The Merchant of Venice”

I hold the world but as the world, Gratiano,

A stage where every man must play a part,

And mine a sad one.

(Antonio, Act 1 Scene 1)

Source for photo: Here

Source for photo: HereShylock, a victim or a villain? Women, empowered or suffused? Is the bond of friendship more powerful than love? Hazard or destiny? Human law or divine justice? Money or Love? Venice and Belmont.

Two Settings

“Venice: the thriving hub of international trade, inhabited by those involved in the cut and thrust of business and commerce. // Belmont: an imaginary setting, a civilised and romantic place, home to the gracious Portia” (Source: Oxford School Shakespeare, “The Merchant of Venice,” 2006)

Money?

In Act I of Shakespeare’s “The Merchant of Venice, “ fortune, which in Shakespeare may mean “luck” as well as “wealth,”grants Antonio a victory by rendering him “Vailing (mast-lowering) Andrew” (Spanish galleon from Cádiz captured by the British). Antonio introduces a debate at stake between material wealth and “ventures not only in one bottom “trusted.”

Fortune / Free Will / Fate / Hazard

Solanio sways from the material to the more elated explanation of presupposing love as the cause of Antonio’s “sadness” or “haziness.” Antonio's continued denial unravels deeper, while Solanio contemplates the immutable truth that our essence is shaped by the cards of fate dealt by nature." ”Nature had fram’d strange fellows in her time; “ Hazard (used in its etymological sense as "randomness") and fate contest to pull characters in divergent paths of understanding.

The choice of caskets is another good example of how hazard, destiny and free will mesh with each other. Portia cannot choose whom to marry, it is only one of the gold, silver, and lead caskets chosen by one of her suitors that will decide her destiny as commanded by her father. Yet, this choice has been contrived by him.

Friendship or Love?

As the play unfolds, Antonio places high stakes on his friendship with Bassanio by offering to accept a contract with Shylock bidding his own life as commodity, a pound of flesh will be cut if he fails to “forteit the bond.”

Equally, friendship surpasses love when Bassanio is ready to dispose of the betrohal ring that Portia offers him as token of their love in exchange for Portia’s services, disguised as a lawyer, in defense of his friend, Antonio. In the amorous subplots, bonds and betrayals ensue. Jessica will be ready to reject his father, and his religion for the love of Lorenzo.

Villain?

In spite of his merciless cruelty upon Antonio, Shylock is also presented as a tragic figure: he is dispossessed of dignity, mocked at, and derided. His claiming for mercy speech turns the balance between villain or victim:

I am a Jew. Hath

not a Jew eyes? hath not a Jew hands, organs,

dimensions, senses, affections, passions? fed with

the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject

to the same diseases, healed by the same means,

warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer, as

a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed?

if you tickle us, do we not laugh? if you poison

us, do we not die? and if you wrong us, shall we not

revenge? (Act 3, scene 1, lines 53 and following)

Women empowered or suffused?

Portia crowns Bassanio lord of her house and heart when radonmness has led him to choose the lead casket, the one that contains the portrait of Portia and the one that will grant him her hand.

Myself and what is mine to you and yours

Is now converted: but now I was the lord

Of this fair mansion, master of my servants,

Queen o’er myself: and even now, but now,

This house, these servants and this same myself

Are yours, my lord. (Act 3, scene 2, lines 165 and following)

Yet, Portia will not relinquish her position of power, “lord of her house,” and disguised as a “lawyer,” she will administer justice to settle the case between Antonio and Shylock. Possible inferences about Elizabeth the Queen might actually be embodied in the character of Portia.

Women trespass the boundaries allotted to them as daughters (Jessica), home-ridden partners as well as the natural barrier between daylight and night time when they rove streets. Women in Shakespeare’s time were played by boys: this double transvestism, boys dressed as women, who dressed as boys remains puzzling as to the role women played in Shakespeare’s works.

Monday 15 April 2024

"The Merchant of Venice" by William Shakespeare

INITIAL THOUGHTS

Tuesday 26 March 2024

Sunday 17 March 2024

"The Piano Player" and "A Little Burst"

"THE PIANO PLAYER " AND "A LITTLE BURST" de Ana María Sánchez Mosquera

Sunday 10 March 2024

"Throwing Ordinary life off Kilter"

Elizabeth Strout’s “Olive Kitteridge”

Source for title phrase here

Source for image: here

“Elizabeth Strout’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book in 2009 “Olive Kitteridge” is not strictly a short story collection, but rather a novel with carefully drawn vignettes of different lives lived in a small fictional community in Crosby on the coast of Maine, a quintessentially New England town. Uniting them all is the formidable figure of Olive Kitteridge, a school math teacher and the wife of a pharmacist. A larger-than-life character, she is at the centre of several stories and peripheral in others” Source: here

Alice Munro described Elizabeth Strout’s novel as “shining integrity and humor, about the bravery and hard choices of what is called ordinary life.” As Reshma Ruia states, “these are the quiet dramas that can throw an “ordinary” life off kilter, one wrong decision or choice that can alter the entire landscape of a life.” Strout reveals loneliness, broken hearts, suicidal drives, ageing, disappointment, the hunger for love and the fact that no one knows everything (“A Little Burst”). In “Starving,” she voices a centripetal axis that may pull these lives ashore, in the words of Winston Churchill: never, never, never, never give up.

The towering, ominous, bulky, and almost statuesque Olive Kitteridge, “ never in anyone’s memory inclined to be affable, or even polite ...”("A Different Road “128) that reveals herself through the story arc hardly appears in the opening story “The Pharmacy.” It is the eyes of Henry that usher us into the novel and through Henry we hear and see Olive. It is in this silence, observed from outside, and from the naïve insecure orderly world of Henry that her character starts to emerge as a powerful binding force of this coastal community. It is in Henry’s fears, pettiness and insecurities that we learn of Olive’s strength, independence and sturdiness.

“For many years Henry Kitteridge was a pharmacist” opens the chapter “The Pharmacy.”The reference to the span of time underpins the paralysis that some of the inhabitants of Crosby resonate with. Seasonal changes occur: colour fading and blooming. Coming and goings of the inhabitants of Crosby run apace with the passage of time. Some elope, some stay stagnant and engulfed by their little and big bursts (nod the chapter that bears the title "A Little Burst"): “You get used to things without getting used to things.” The elopers are missed and the ones that remain gaze empty-eyed through windows of cars, houses, and local stores. Henry’ s sense of self-complacency in his small pharmacy world contrasts with the shady description he makes of his wife:

“Retired now…. He remembers how mornings used to be his favourite, as though the world were his secret, tires rumbling softly beneath him…. The ritual was pleasing, as though the hold store...was a person altogether steady and steadfast.”

Objects, places seem to vividly shape the souls of the community. The piano in “The Piano Player” is not just an instrument, it is a character in the room. Whereas Henry shines in his small orderly world of vials caressed by a dappled sun, Olive first appears as “And any unpleasantness that may have occurred back in his home, any uneasiness at the way his wife often left their bed to wander through their home in the night’s dark hour...” (2). He watches that she does “not bear down too hard on Christoper.”

Henry’s infatuation with his pharmacy assistant, Denise, is peremptorily accepted by Olive. She shifts from derision”Handwriting is as cautious as she is ...she is the plainest child I have ever seen. With her pale coloring, …”(13) to indifference. Yet Henry acknowledges this powerful binding to Olive as a bastion of his life “...women are far braver than men. The possibility of Olive’s dying and leaving him along gives him glimpses of the horror he can’t abide” (18). As the possibilities of a liaison with Denise fleet before his eyes, he desires Olive “with a new wave of power. Olive’s sharp opinions, her full breasts, her stormy moods and sudden, deep laughter unfolded within him a new level of aching eroticism” (11). It is Henry’s tantalizing affair that reveals Henry’s own fears of solitude: “You’re not going to leave me, are you?” (he asks Olive).

Sunday 25 February 2024

Wednesday 14 February 2024

"A poet in Mars: The Martian Chronicles by Ray Bradbury"

A book Review by Cándido Pintos Andrés

"A poet in Mars: The Martian Chronicles by Ray Bradbury"

Photo by Cándido Pintos

Rather than just an author of Science Fiction, Ray Bradbury is a writer in capital letters. In The Martian Chronicles, Bradbury shows us a collection of short stories of deep reflections on humanity and society, with the disguise of the colonization of Mars, when he is really talking about destruction and decay. Along the book, and apparently through the different expeditions to Mars, the author addresses the problem of racism, religion, the expansion of capitalism, the machine-age utopia, the future of technology, loneliness and solitude. In fact Mars, as the multiple rockets of the story, is just a means and the book could be entitled The American Chronicles with just a few changes and new descriptions

But he is also a visionary, and his stories are a showcase for both future technology (“Mr K himself in his room, reading from a metal book with raised hieroglyphs over which he brushed his hand, as one might play a harp. And from the book, as his fingers stroked, a voice sang, a soft ancient voice, which told tales ..”) and the threats posed by this technology against its creators (“The house was an altar with ten thousand attendants, big, small, servicing, attending, in choirs. But the gods had gone away, and the ritual of the religion continued senselessly, uselessly”)

Ray Bradbury writes with evocative language and masters creating emotional atmospheres with a prose touched by poetry. If not among the best, one of the most influential writers of his generation, inside and even outside the literary world, despite the fact that “We earth men have a talent for ruining big, beautiful things.”

Cándido Pintos Andrés

Friday 9 February 2024

Of Mistresses, Coyness and Metaphysics

John Donne’s “To his Mistress Going To Bed” (1669)

and

Andrew Marvell’s “To his Coy Mistress” (1681)

This post will aim at providing a comparative insight into John Donne’s poem “To his Mistress Going to Bed” (1669) and Andrew Marvell’s “To his Coy Mistress” (1681), both considered Metaphysical poets. Both poems are addressed to “their mistresses” rather than their “ladies,” or “wives.” The word “mistress” had different connotations at the time:

‘Mistress’ in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries normally designated a woman of higher social standing without any marital connotation, whether married or unmarried. It could also be applied to women of dubious sexual reputation. (Paraphrased from: History Extra and Mistresses and marriage: or, a short history of the Mrs )

Both mistresses constitute the target of their lover’s amorous requests so they can win their favours regardless of whether married or not, whether they are of high-standing or dubious sexual reputation. They are both the objects, the commodities, the target of the poetic voice verbal pyrotechnic. In Donne’s, the poetic voice exhorts his mistress to go to bed with him, and in Marvell’s, the poetic voice beckons his mistress to seize the day and yield to his requests because they have not “the world nor the time.” Marvell’s poem elaborates on the trope of “memento mori,” the urgency to seize the moment, given the transience of human nature.

In Donne’s poem, the convincing arguments and elegiac tone ( wooing his mistress favours) lay grounds for his verbal witticisms. He juxtaposes warfare imagery (foe, labour, breastplate) with Petrarchan deconstructed idealization: “heaven’s zone glistering but a far fairer world encompassing,” “the happy busk” he envies and that reveals “such beauteous state.” The erotic blends with the religious, as seen in the "hallowed temple" or "Mahomet's paradise." His mistress is envisioned as a new found land, his America. The commodification is rounded as she becomes a territory to be explored, a land to be conquered. After making his case, and on apparently false pretense of equity, the poetic voice instances his mistress to: “show Thyself; cast all, yea, this white linen hence, Here is no penance, much less innocence” and “To teach thee, I am naked first.”

In Marvell’s poem, the word “coy” indicates that perhaps no strenuous convincing argumentation will be needed. “Coyness” makes allusion to false pretense of shyness. The poetic voice makes a case about time and the transience of life, “memento mori,” and therein, the need to make most of her youth, “thy skin like morning dew” and cast away her “long-preserved virginity.”

“Had we but the world and enough time ….But ,,,,” they don’t and “while the youthful hue //Sits on thy skin like morning dew” (while she is still young) “Let us roll all our strength and all / Our sweetness up into one ball..”

As in Donne’s poem, we can also find references to far away lands: the Indian Ganges, empires, gems, and precious stones, a nod to colonialism once more, a larger setting that taps into conquering and possessing. Religious imagery is present here as well as it can be seen in references to the flood, and the conversion of Jews. As a counterpart to these promises of love, there is in “To his Coy Mistress,” the urgency and the overshadowing presence of death as suggested in the “marble vault,” and the putrefaction of the “body”: “the worms shall try.” “They cannot make their sun / Stand still, yet we will make him run” ( a possible reference to “Phaeton and the Sun Chariot”, both an image of death and youth). Eros kai thanatos is a common literary motif: love and death go hand in hand.

Whether a more satiric approach in the case of Marvell’s “To his Coy Mistress,” or a more sillogystic analysis of emotions in Donne’s “To his Mistress Going to Bed,” both poems share the brazen irony, and the juxtaposition of impossible elements through metaphors and similes as well as the analytical approach of the spiritual or less tangible that define Metaphysical poetry.

Sunday 4 February 2024

Monday 29 January 2024

Saturday 27 January 2024

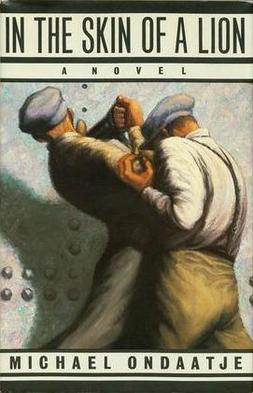

"In the Skin of a Lion" (Michael Ondaatje)

Caravaggio: more than a character in “In the Skin of a Lion" (1987)

by Michael Ondaatje

A Review by Begoña Rodríguez Varela

In Michael Ondaatje´s “ In the Skin of a Lion”, indeed, the independent likable character, painted in blue so he can camouflage in the dark and become a burglar, introduces himself as “ Caravaggio- the painter.”. The brilliant Baroque artist imbued his fabulous paintings with great theatrical drama and emotion thanks to his use of extreme contrast of darkness and light, his Chiaroscuro. However in this novel” the dark” reveals itself as a symbol of concealment, of secrecy, whereas the few sources of light, cattails, lanterns or candles, are symbols of life, of dynamism. Only at the end, the light floods in and everything comes alive.

Also, both authors, Caravaggio and Ondaatje share the idea that, to give a real picture of religious / historic events, those unhistorical forgotten people should undoubtedly be given their right place. All of them are also God´s people. Marginal and central figures together. Nice tableau.

Thereby the novel is made up of the intertwined, interconnected stories of a few of the members of those communities of migrants who participated in the construction of Canada: the waterworks, the tunnels , the bridge. It was the Commissioner Harris who had envisioned it. It was them who made his dream come true. No record was kept of those thousands who lost their lives then, though. Blankness.

Among those workers is Patrick Lewis, the protagonist, always in the shadows, alone, self-sufficient. He works as dynamiter of jam logs in the harsh countryside of Eastern Ontario and, then, as a searcher in Toronto, where he meets Caravaggio, the thief, for the first time. Afterwards, while in prison, Patrick would save his life. His first step towards authentic human connection. Friendship.

Later on, both solitaries, who fight against the privileged class violently, devise a plan together to blow up the waterworks. Now Caravaggio is the helping hand and Patrick, the one who swims in troubled waters.

However, after his encounter with Harris, the sunlight fully illuminates the scene. It is then that Patrick understands that no legitimate cause justifies violence, not even the death of just one human being, the Commissioner. Patrick finds his true identity ….at last.

Eventually , in broad light he starts a journey with Hanna, his late partner´s daughter to Marmora, where his first lover awaits him. But that will be the beginning of another story, different from Caravaggio´s, his friend, who disappeared in darkness.

By @caravaggio72

Sunday 21 January 2024

"My Oedipus Complex" by Frank O’Connor (1963) and “Araby” by James Joyce (1914)

Fantasies at War

My Oedipus Complex by Frank O’Connor (1963) set in the close of World War I and Joyce’s Araby (Dubliners, 1914) set in Dublin in times of cultural and religious colonization of Ireland by Great Britain (Pedram Manieem, Shahriyar Mansouri) revolve around stories retrospectively rendered from the perspective of childhood. Lines can be drawn between both stories as to how the narrators´ perception of the world is presented with irony and an underlayer of political, social and economic circumstances.

Larry’s father comes and goes, unnoticed, like Santa Claus in his uniform, disguised in this fantasy, Larry copes with his father’s “mysterious entries and exists.” The war, “ he says, “is the most peaceful period of his life.” The absent father, noticeable for his “amiable inattention,” returns home in the aftermath of the war and ”usurps” his place in the fondness and attachment he feels towards his mother. He must keep quiet, not disturb his father. He is ostracized from the thalamus. It is the first time he hears those “ominous words,” “talking to Daddy.” God is to be blamed for listening to his prayers. Economic hardships wax the tension in the family: no more money at the post office and a bedridden unemployed dad that suffers from shell shock (post traumatic syndrome suffered by many soldiers affer the first war) coalesce to pinpoint the paralysis of the times. An epiphanic moment occurs when the new baby arrives and Larry and his father meet in their own displacement from the mother’s contesting attention.

In James Joyce’s Araby, the protagonist lives under the aegis of his uncle and aunt in an equally oppressive atmosphere as the opening of the short story illustrates, blindness and imprisonment being metaphors for it:

"North Richmond Street, being blind, was a quiet street except at the hour when the Christian Brothers' School set the boys free."

"On Saturday morning I reminded my uncle that I wished to go to the bazaar in the evening. He was fussing at the hallstand, looking for the hat-brush." (“Araby”)

See the political implications of this quote in this other passage from “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man” by James Joyce: Dante [his grandaunt] had two brushes in her press. The brush with the maroon velvet back was for Michael Davitt and the brush with the green velvet back was for Parnell." (A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man)

"I'm afraid you may put off your bazaar for this night of Our Lord."

The narrator’s fantasy of “Araby,” as an exotic escape from this darkness is already frustrated: politics, religion and oppressiveness will impede the fulfilment of his desires. He is doomed from start: his uncle is late for him to go to the bazaar, religion acts as a constraining force, and his pride will stop him from sparing his money out. The house where they live, he says, belongs to a priest. This priest refers to another short story “The Sisters” (Dubliners), connected with the sin of simony ( trafficking with religious objects).

The narrator’s first infatuation with Mangan’s sister will forcefully drive him to the bazaar, “Araby,” on an errand to buy her some token. Both Araby and his first love are wrapped in a foggy halo of fantasy:

I looked over at the dark house where she lived. I may have stood there for an hour, seeing nothing but the brown-clad figure cast by my imagination, touched discreetly by the lamplight at the curved neck, at the hand upon the railings and at the border below the dress.

When he arrives, the bazaar is closed. he listens to two men speaking in a foreign accent, “English,” and full of pride, he recoils from the prospect of buy anything.

I lingered before her stall, though I knew my stay was useless, to make my interest in her wares seem the more real. Then I turned away slowly and walked down the middle of the bazaar. I allowed the two pennies to fall against the sixpence in my pocket. I heard a voice call from one end of the gallery that the light was out. The upper part of the hall was now completely dark.Gazing up into the darkness I saw myself as a creature driven and derided by vanity; and my eyes burned with anguish and anger.

Irony, humour, innocence and growing pride understate and conversely highlight the frustrated fantasies that both narrators undergo in their harsh encounter with the social and political turmoil of the times.

Saturday 13 January 2024

"C.S. Lewis versus Paul Auster"

Sometimes a book calls you up at the right moment. More than twenty years ago the film “Shadowlands” was recommended to me by a friend, after a long talk about God and grief. My love for Debra Winger did the rest; that is how I found C.S. Lewis and “ A Grief Observed.”

The nights of this grey and rainy autumn were a fabulous opportunity for pulling out of the drawer many films and songs almost forgotten: “Smoke” was the chosen one.

“Smoke” is an independent film from 1995 directed by Wayne Wang and based on a story written by the American author Paul Auster, whose short story “Auggie Wren's Christmas Story” plays an essential role in one of the best and most highly known scenes.

So, with the fresh reading of “A Grief Observed” and Paul Auster unconsciously in my mind, another greyish evening led me to a bookshop and, once among the shelves, my eyes focused instinctively on the last book by Paul Auster: “Baumgartner.” And I bought it

In “Baumgartner,” Paul Auster offers a tender reflection of loss, memory, and grief in such a way that I could not help but think that Paul had been in our reading workshop last week and had rewritten, with other words, many of the paragraphs of C.S. Lewis’s book.

“Did you ever know, dear, how much you took away with you when you left? You have stripped me even of my past, even of the things we never shared. I was wrong to say the stump was recovering from the pain of the amputation. I was deceived because it has so many ways to hurt me that I discover them only one by one.” (Lewis)

“He is a human stump now, a half-man who has lost the half of himself that had made him whole, and yes, the missing limbs are still there, and they still hurt, hurt so much that he sometimes feels his body is about to catch fire and consume him on the spot.’ (Auster).

"And grief still feels like fear." (Lewis)

"To live is to feel pain, he told himself, and to live in fear of pain is to refuse to live. "(Auster)

"I had yet to learn that all human relationships end in pain" (Lewis)

“(...) to be as deeply connected as they were when she was alive can continue even in death for if one dies before the other, the living one can keep the dead one going in a sort of temporary limbo between life and not-life, but when the living one also dies, that is the end of it (...) ”(Auster)

So ..was this book calling me up? I will never know it but the fact was that I felt I had closed the circle.

Links:

- “Shadowlands”

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0108101/?ref_=ext_shr_lnk

https://youtu.be/NLKS0XGRYi8?si=BGwKj81gj1MBSNyJ

- “Smoke”

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0114478/?ref_=ext_shr_lnk

https://youtu.be/3v8r-ec4V2M?si=hSd2JLiRDmsO_PMH

- “Auggie Wren's Christmas Story” by Paul Auster (just 5 pages ! )

http://www.xtec.cat/~dsanz4/materiales/auggie_wren.pdf

- Auggie Wren's Christmas Story (scene of “Smoke”)

https://youtu.be/_kCUbw8Ug28?si=9xpOWizeQ7AmU0wA

- New York Times review: Auster and C.S.Lewis

https://lithub.com/5-book-reviews-you-need-to-read-this-week-11-9-2023/

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/06/books/review/paul-auster-baumgartner.html

By Cándido Pintos Andrés

--

Monday 1 January 2024

"The Merchant of Venice"

"The Merchant of Venice." The Way you See it. de Ana María Sánchez Mosquera

-

“ The Bear,” a review by Begoña Rodríguez Varela “ Into the wind” By Marion Rose (Pic chosen by Begoña Rodríguez Varela) . Click here f...

-

“ HAMNET: Transfiguration of Life into Sublime Art” by Begoña Rodríguez Varela “ Hamlet and the spectre” By Eugène Delacroix : click ...

-

Caravaggio: more than a character in “In the S kin of a L ion" (1987) by Michael Ondaatje A Review by Begoña Rodríguez Varela In ...