THE RIPPLE

in

Face by Alice Munro

Keywords: Birthmark, drama, judgement, relationships, what if… Click here to read the story in “The New Yorker.”

“Face,” the title that the short story honours, is a decoy for a more expansive ripple (other than the visible “face”): selfhood, relationships between children, adults, peers and the muted voice of a vitriolic community .. . The narrator is physically “branded” from birth by a mark on his face. The narrator ushers us into the journey of his selfhood through the overstretched sinews of his family life. His father rejects him from birth as “ a chunk of chopped liver,” his mother protects him by endorsing “his” birthmark as a token that will make the “white of that eye look so lovely and clear “ and which he adds,”was one of the idiotic though pardonable things my mother would say.” Rejected by his father and protected by his mother, the narrator undermines all judgement: “One side of my face was—is- normal. And my entire body was normal from toes to shoulders...My birthmark not red, but purple.” This retrospective narrator stands rationally athwart between his father’s derogatory treatment and his mother’s aegis.

His clinical incisiveness by referring to his physical appearance from a rational point of view, his right away rejection of his father’s conception, his subtle allusion to a voiceless body of an omnipresent community, as in many other Alice Munro’s stories, “a son, which is presumably what all men wanted” wage war about the expansive wave of many of the other connections that will take place in the short story. The rift between his parents is older than him: “In all my years in the town, I encountered no one who was divorced, and so it may be taken for granted that there were other couples living separate lives in one house” (141)

In town, people said “she was beautiful, some people told me” (page 140) and also, they say (he) ”Calls a spade a spade. That was what was said of him” (140). In this place, “hate and despise are customary.”

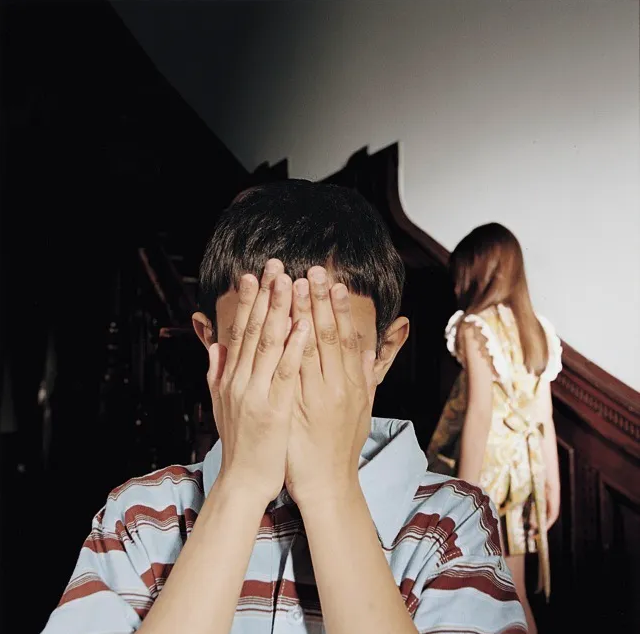

This is the drama of ordinary lives, children call each other names Grape-Nuts, Stink, His Grace… Pete has been to the war and he is now a gardener with a limp, who is called nazi by Nancy and the protagonist to serve their random fancies. Nancy cruelly paints her face red to imitate the protagonist, who comes to a terrible realization that his birthmark might be that red, but, who does not take it as badly as his mother who goes berserk and vents her wrath through the many tentacles of hidden pain. She snips gladiolos in a frenzy, because she cannot hold Sharon nor Nancy any longer, She cannot longer swallow the infidelity of her husband with Sharon, “Sharon dewy rose” as the hymn at school went. The birthmark expands the ripple through the innards of less visible pain. This is about the great drama of Nancy who looks for connection and cuts her face with a razor to mirror the narrator. They both had feelings, “such deep feelings. Children have,” because they have both listened to “Alice in Wonderland’s stories” and wonder about the potions that might be poisoned and make you smaller so you can fit through the hole. Nancy’s father died of blood poisoning.

This is the “Great Drama,” as he calls it, which is not really a drama, but lives, a life, a job indeed, the narrator’s job as an actor: “my voice stood me in good stead,” he says. Another voice stands him in good stead when stang by a wasp, at hospital, and blindfolded, he listens to familiar narratives he knows, read to him by a mysterious reader. There is only one he is not familiar with and which he finds among weathered pages, and probably "buried in a deep cubbyhole of his mind": Walter de la Mere`s. Walter de la Mere's poem bespeaks of time that does not really heal, and absence.

You may never come across what you have left behind, but what if …. “the answer is of course, and for a while, and never”