"I / eye: The Dismembered Body and the Dismembered Mind"

in Edgar Allan Poe’s

“The Tell-Tale Heart”

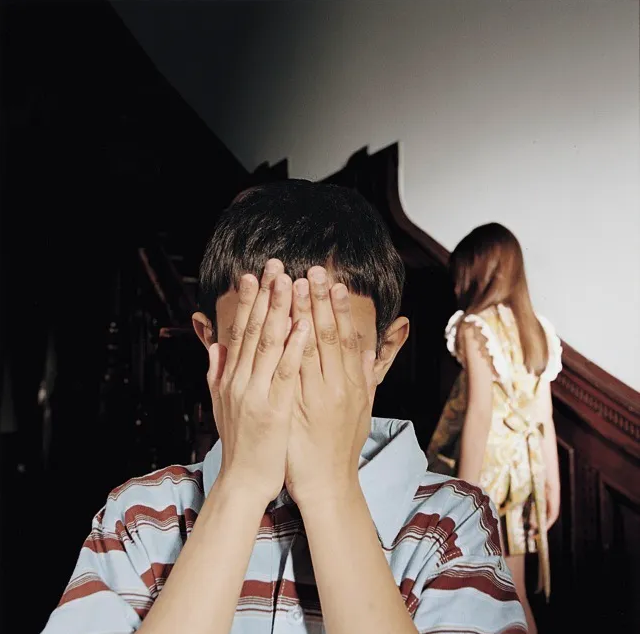

Source for photo

“Barrie Kosky's second appearance at the International festival could not be more different from his debut last year...his meticulous staging of Edgar Allan Poe's short story The Tell-Tale Heart is pitch black, tense and savage. The curtains open to reveal the apparently disembodied head of performer Martin Niedermair, hovering in an unnerving silence ...Poe's narrator claims he is not mad, but suffers an "over-acuteness of the senses". Such is the condition that Kosky inflicts on his audience. We become painfully aware of the noises that escape from Niedermair as he describes how he came to murder an old man: the slick of his tongue against his chin, the hiss he emits as he dismembers the corpse; even the slap of his hands against his thighs is discombobulating”

https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2008/aug/11/theatre

(Edinburgh International festival 2008)

Little I remember of this performance, but one image still clings forcefully to my mind and I remember through the dust of memory, the shadow of a man, sometimes on a chair, more dramatically on the stairs, surrounded by a pitch black stage with an occassional intense light showering on him. I now fancy this silhouette cutting the empty darkness with protruding veins on his throat and raving eyes. The oppressive animated movie narrated by James Mason and directed by Ted Parmalee in 1953 (here) has played the tune of remembrance hand in hand with this performance.

What is madness if not an over acuteness of the senses: the ticking of the clock, the beating of the heart, the creaking of doors, the prodding conscience, the eye / I, the vulture I/ eye that disturbs the narrator. It is the old man’s I/ eye that obsesses the narrator, not greed, not his wrong-doing. It is the eye/ I that triggers the murderous instinct and sets the narrator’s plan in motion: to get rid of the old man. In the process, the reader must be won over as a convinced acolyte of the narrator’s sanity and witness to his/her minute and stealthy ways. "Excusatio non petita accusatio manifesta."

One might say that what bothers the narrator in this equation of onomatopeic resemblance between the two words eye /I might be “the otherness” of the old man. The multiple selves of the schizophrenic mind may provide grounds to read the narrator’s obsession with the old man as a possible projection of his/her own self , a self that s/he may not want to come to terms with or cannot, a self that is possessed / evilized by something larger than itself. The narrative voice states that “ this idea entered my brain.” The idea becomes bigger and more materialized than the narrator, who seems to be an unreliable bodiless mass of highly interjected words and sentences, proof of the nervous state in which this conscience flounders.

The gender identity of the narrator has also been discussed. By the end of the nineteenth century, there existed accentuated double standards for men and women. Women were commonly associated with roles of nurturers, caregivers and guardian angels of the hearth. Gothic narratives and nineteenth century novels often challenged openly or more seclusively these double standards and, as a result, a paralell narrative of fallen women ensue. Women characters were prone to appear as deranged women, suffering nervous breakdowns, torn asundered by the so called moral standards. All of these fed the imagination and kept the guardians of the moral at bay by separating the intricacies of doublefolded nature. A discussion of whether Poe's narrator might be a woman will certainly fuel a quarry of interpretation regarding the roles of women at the time.

Sonia pointed out the phrase: “You fancy me mad. Madmen know nothing” where the diatribe about the marked gender narrator might be conclusive.

Some of the readings held in our discussion were really interesting: the “scantlings” on the floor where the narrator hides the dismembered body (Belén Tizón) have the shape of a cross, or the title has been interpreted as an onomatopeia of the ticking of the clock through the use of the alliterative “t” (Belén Tizón), the reference to the use of the word “tale” as in “fairy tales” (Liam) and its possible implications. Is the presence of the “eye” the eye that sees it all, the presence that wants to exert control...? (Begoña’s thesis).

Engage in the thread and post your insightful readings:)