Thursday 30 December 2021

The Gothic by Professor John Bowen

Sunday 19 December 2021

Friday 10 December 2021

"On Beauty and Being wrong" (Part III)

On Beauty and Being Wrong (Part III)

“Ah-a Hopper,” said Kiki, pleased at the coincidence. It was a print of Road in Maine, one of the series of poorly reproduced lithographs of famous American paintings meant to signal the classiness of the store ...”Someone's just walked down there,” she murmured, her finger travelling softly along the flat, paintless surface. “Actually, I think it was me. I was moseying along counting posts. With no idea where I was going. No family. No responsibilities. Wouldn't that be fine! “Let's go to Amherst,” said Carlene Kipps urgently.(“On Beauty” (end of section 2, “The Anatomy Lesson,” page 268)

The bond between the two ladies, Carlene and Belsey, has by now narrowed in their sparse encounters, and , consolidated through an inarticulated reality of common understanding and unison. This intrinisic reality (equally attributed to this Hopper's landscape) surpasses the ideological confrontation of their respective partners for the sake of beauty, embodied in their joint admiration for the “The Maitresse Erzulie” painting which Carlene shrines in her house; an undermining of academic verbal pyrotechnics and the prospect of embarking themselves on this Amherst adventure with “no responsibilities”. However, the likelihood of this occurrence is curtailed by the uneventful apperance of Carlene's son, Michael, and husband, Mr Kipps. Amherst, Emily Dickinson's hometown and burial place, constitutes one of the many strewn references to Emily Dickinson in this novel.

“I Died for Beauty,” written by Emily Dickinson acquires utmost relevance at this crux between section 2 and section 3:

I died for beauty, but was

scarce

Adjusted in the tomb,

When one who died for truth was

lain

In an adjoining room.

He questioned softly why I failed?

"For beauty," I replied.

"And I for truth -

the two are one;

We brethren are," he said.

And so, as

kinsmen met a-night,

We talked between the rooms,

Until the

moss had reached our lips,

And covered up our names.

“On Beauty and Being wrong” opens up with Carlene's death, burial, wake and legacy to Kiki, the painting by Hector Hyppolite, “The Maitresse Erzulie.” The Kippses reluctance to grant Kiki the painting and its concealment set the “deus ex machina” of the narrative in motion. Levi will set the balance right by returning the painting to its origins through his own political activist crusade with the Haitians.

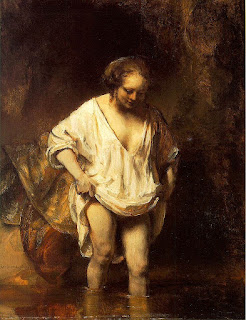

“On Beauty and Being Wrong” also lingers on Howard's struggle with his own insecurities, his middle-aged crisis, his being wrong and wanting to be right, his infidelities, his re-reading of Rembrandt, his re-reading of love, his dissension with academia, his misinterpretations and misencounters. He travels back through the stranded road of time to encounter his father, the butcher, who wanted him to write about beautiful things that may have enlightened his mother, the woman they both loved and the only thing in common. He storms out to discover that time has congealed misunderstanding.

Carl, the street poet, the lyricist, ascends the podium of academia. He is allotted a nook in the library archive, in the Department of Black studies, but the system stifles him. He banishes from the narrative after a misalignment of stars. Victoria´s overpowering beauty snowballs disaster: the unfortunate matches-- Howard and Victoria, Carl and Victoria, Victoria and Zora, Victoria and Jerome-- ensue chaos. Monty is equally unmasked and exposed in a faux pas of not communing with his preaching.

The novel ends with Howard's contemplation of this painting:

“Hendrickje Bathing, 1654,’ croaked Howard and said no more... The woman’s fleshiness filled the wall. He looked out into the audience once more and saw Kiki only. He smiled at her. She smiled. She looked away, but she smiled. Howard looked back at the woman on the wall, Rembrandt’s love, Hendrickje. Though her hands were imprecise blurs, paint heaped on paint and roiled with the brush, the rest of her skin had been expertly rendered in all its variety – chalky whites and lively pinks, the underlying blue of her veins and the ever present human hint of yellow, intimation of what is to come.”

Go ahead and post your comments on the gnarling of this section!

Saturday 4 December 2021

Saturday 27 November 2021

KIPPS AND BELSEY (Part 1 "On Beauty" by Zadie Smith)

KIPPS AND BELSEY

(On Beauty by Zadie Smith)

(Session 25th November)

Upon a first approach to Zadie Smith, we have come across what James Wood denominates “hysterical realism” in his article, ”Human, all too Inhuman” (The New Republic, 2000 ), a pressing , emergent and “harding” genre in the narrative of current novels. Zadie Smith is mentioned among the many names to whom this “hysterical realism” might be attributed . As we understand, hysterical realism dwells on sometimes impossible interconnected and overdetailed characterization in a search for a human and “realistic” approach to character depiction and narrative events, but, which, contrariwise to its pursued effects, results in impossible connections, far-fetched liaisons and shallow waters.

Ready for this Dickensian “puppetry” that James Wood mentions and, with minds formed to it, we break through the world of the Belseys and Kippses in Zadie Smith’s novel On Beauty, awarded the Orange prize in 2006. Yet, the chalant warning flounders in the careful “scaffolding” (a word that Zadie Smith uses herself to explain her process of writing) of the two families, Kipps and Belseys; two places, London and the fictional University town of Wellington near Boston; two political and spiritual mindsets (conservative and liberal, Christian and atheist) that will conform the tapestry of the novel.

The first part of the book dwells more on the Belseys than on the Kippses, indeed, there is no direct access to the Kippses but, through the perspective of the Belseys. Jerome, the sensitive Belsey’s son, opens up a narrative on “beauty” with unpoetic and unanswered emails from the Kippses household addressed to his father to announce his wedding with Victoria, the Kippses’ daughter. Howard embarks on a swift journey to London to stop the marriage, questions of religion at stake, but, a last email heaves through the “electronic machine waves” and only Kiki, the matriarch of the Belsey family, knows that the prospective marriage has already been written off.

Vitriolic criticism sheathed in humor key preys on the phoney world of intellectuals and academics. Liberal and atheist Howard, originally from England, is in dispute with the conservative and Christian Monty, originally from Trinidad. They are both Art History professors, both working on Rembrandt. Whereas Howard’s book on Rembrandt remains unbound, strewn and unfinished, his colleague’s has been published. Howard has shamed himself in front of the academic community by confusing Rembrandt’s “Self-Portrait” (Munich) with “Self-Portrait with Lace Collar” (The Hague) which Monty mentioned in his research.

Academic elitism dovetails with racial and gender issues: Carle, a rap poet, who attends a classical music recital (Mozart’s “Requiem”), wanders as an outcast in the circle of the intellectual elite. Kiki, with Afro-American origins, is also an outcast in the intellectual world of Howard, but, constitutes the first glimpse of beauty and authenticity in the novel. The Belsey’s home is really Kiki’s inherited home, nothing “nouveu riche” about it, and, which, in spite of its shabbiness, constitutes a bastion of her sturdiness. Pictures of Kiki’s ancestors through the staircase constitute a counterpoint to Howards’ ridicule Bermuda pictures, or his baseball cap photograph pointing towards Emily Dickinson’s house. Infidelity also lashes out within the cultural constructs of this world.

Interesting intertextual references to search for in this first part of the novel: John Cheever’s short story “The Swimmer,” (see story in The New Yorker, click on title) the importance of Mozart’s “Requiem”, Rembrandt’s “Self-Portrait” (Munich) and Rembrandt’s “Self-Portrait with Lace Collar” (The Hague).

Saturday 20 November 2021

On "The Lazy River" by Zadie Smith

Session 18th November

Some Keywords: Metaphor (μεταφορά), Short form, Circular Flow, Heraclitus, Social Media, Migration, Brexit.

Zadie Smith's “The Lazy River” was first published in The New Yorker , December 2017. One reads the title and does not expect the despair and hopelessness that lies ahead. Incantations of idleness and a Huck Finn journey acrosss the Mississippi, on long Sunday evenings, crosses the mind. Instead, hazy and disquieting borderlines spring as the eye wanders through the opening background blurry illustration by Geoff McFetridge which depicts a faceless lady adrift on a “buoyant” floating device.

More confusion lies ahead with the genre: an explanative metaliterary approach imbibes the reader inside the word “metaphor” and thrushes us into the narrative. “We” become part of the journey that leads nowhere. We find ourselves emmeshed in a circular journey, on an unnamed river, inside a metaphor that gives the impression of flow but leads us to the the starting point. It should not pass unnoticed that the word “metaphor” comes from the Greek μεταφορά (meta-behind, along / ferein: carry), which means “transfer,”” transference from,” “journey from one word to the other” which brings us back to the original.

We wonder whether this short form shapes into fantasy, essay or article. Clichés of British holidaymakers in Southern Spain twist into further depths, at least,“three feet depth.” The narrative voice wanders around the empty rituals they perform: lounging around the lazy river, letting themselves go with the flow; some carry buoyant floating devices, under the same relentless sun, forever, never advancing: others resist the ”ouroboros” thrashing a stroke, but finally yielding to the heraclitean curdled flow.

These holidaymakers do not venture the vast ocean, nor the Moorish ruins, nor the arid mountains, “nor infinite horizons.” They do not venture into unknown territory. The fascinating literary journeys are replaced by sudokus, they gobble at the buffet, but, this is a non-judgemental zone, the narrative voice claims. Yet, there is stealthy shame that arises in between the lines. Shame is a concept that Zadie Smith brings forward in this interview.

Go ahead and comment on any of the issues above that arose in our last session, and, to which you contributed,as usual, with sharp insights and wonderful readings.

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances;

And one man in his time plays many parts,

(Shakespeare, “As you Like it”)

"The Merchant of Venice"

"The Merchant of Venice." The Way you See it. de Ana María Sánchez Mosquera

-

“ The Bear,” a review by Begoña Rodríguez Varela “ Into the wind” By Marion Rose (Pic chosen by Begoña Rodríguez Varela) . Click here f...

-

“ HAMNET: Transfiguration of Life into Sublime Art” by Begoña Rodríguez Varela “ Hamlet and the spectre” By Eugène Delacroix : click ...

-

Caravaggio: more than a character in “In the S kin of a L ion" (1987) by Michael Ondaatje A Review by Begoña Rodríguez Varela In ...