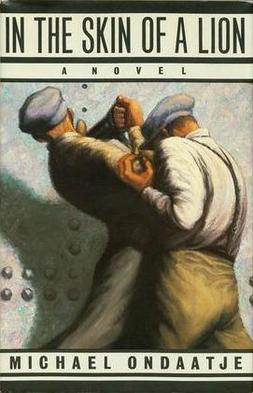

Caravaggio: more than a character in “In the Skin of a Lion" (1987)

by Michael Ondaatje

A Review by Begoña Rodríguez Varela

In Michael Ondaatje´s “ In the Skin of a Lion”, indeed, the independent likable character, painted in blue so he can camouflage in the dark and become a burglar, introduces himself as “ Caravaggio- the painter.”. The brilliant Baroque artist imbued his fabulous paintings with great theatrical drama and emotion thanks to his use of extreme contrast of darkness and light, his Chiaroscuro. However in this novel” the dark” reveals itself as a symbol of concealment, of secrecy, whereas the few sources of light, cattails, lanterns or candles, are symbols of life, of dynamism. Only at the end, the light floods in and everything comes alive.

Also, both authors, Caravaggio and Ondaatje share the idea that, to give a real picture of religious / historic events, those unhistorical forgotten people should undoubtedly be given their right place. All of them are also God´s people. Marginal and central figures together. Nice tableau.

Thereby the novel is made up of the intertwined, interconnected stories of a few of the members of those communities of migrants who participated in the construction of Canada: the waterworks, the tunnels , the bridge. It was the Commissioner Harris who had envisioned it. It was them who made his dream come true. No record was kept of those thousands who lost their lives then, though. Blankness.

Among those workers is Patrick Lewis, the protagonist, always in the shadows, alone, self-sufficient. He works as dynamiter of jam logs in the harsh countryside of Eastern Ontario and, then, as a searcher in Toronto, where he meets Caravaggio, the thief, for the first time. Afterwards, while in prison, Patrick would save his life. His first step towards authentic human connection. Friendship.

Later on, both solitaries, who fight against the privileged class violently, devise a plan together to blow up the waterworks. Now Caravaggio is the helping hand and Patrick, the one who swims in troubled waters.

However, after his encounter with Harris, the sunlight fully illuminates the scene. It is then that Patrick understands that no legitimate cause justifies violence, not even the death of just one human being, the Commissioner. Patrick finds his true identity ….at last.

Eventually , in broad light he starts a journey with Hanna, his late partner´s daughter to Marmora, where his first lover awaits him. But that will be the beginning of another story, different from Caravaggio´s, his friend, who disappeared in darkness.

By @caravaggio72